- It is crucial that candidates with sensory impairment are able to show what they know and can do without changing the demands of the assessment.

- Having an impairment does not entitle the candidate to any specific arrangements they wish to have — it has to be shown that the candidate needs them.

- It will not normally be considered reasonable for adjustments to be made to the assessment objectives within a qualification.

- Any request must reflect the candidate's normal way of working in the classroom.

- Embarking on a course does not automatically mean that the qualification at the end of it can be made accessible.

- Support needs to be carefully controlled to ensure that what is assessed is the candidate's own knowledge and understanding.

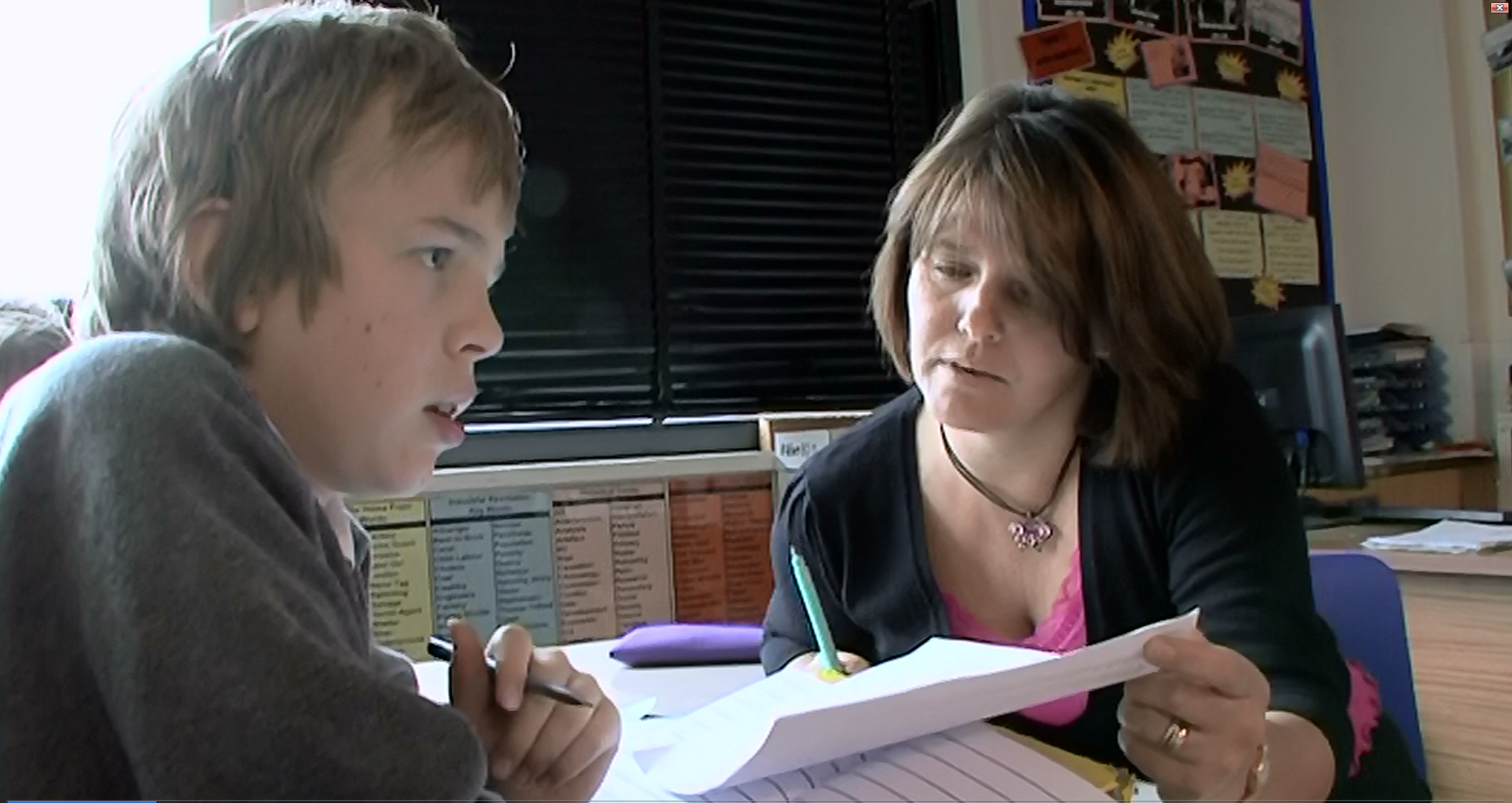

In this video extract, Graham Carter and Rory Cobb give an introduction to access arrangements.

Although they are speaking specifically about vision impairment, the principles apply equally to hearing impairment.

Select this link for a transcript of the video clip.

Removing barriers

The implications of a sensory impairment on all aspects of learning and development are well known to teachers of children and young people with HI, VI and MSI. These same factors can also have a significant effect on the formal assessment of these learners' skills, knowledge and understanding.

It is crucial that candidates with sensory impairment are able to show what they know and can do without affecting the integrity of the assessment and that any barriers to their being able to do this are removed or mitigated.

Entitlement

The concept of creating a level playing field by minimising the 'long term and substantial adverse effect' of a disability on a candidate's performance is clear. It is important to stress to colleagues and others not in the field that this should not be thought of as giving students 'concessions' but rather as meeting their entitlement to reasonable adjustments in the light of the effects of their disability.

Access arrangements are the principal way in which awarding bodies comply with their duty under the Equality Act (2010) to make 'reasonable adjustments'. They are intended to remove or minimise disadvantage, whilst not giving the candidate an unfair advantage. They are not granted automatically, but should be a response to the identified effects of an individual candidate's disability on their access to assessment.

Demonstrating need

Having a hearing or vision impairment does not entitle the candidate to any specific arrangements they wish to have — it has to be shown that the candidate needs them as a consequence of their disability. This is achieved by 'painting a picture of their needs', explaining the effects of the sensory impairment on them and providing evidence to support this, including where appropriate the results of standardised testing. Further information about these principles and processes is given in the activity 'Evidence of need'.

The definition of a reasonable adjustment is not straightforward and depends on individual circumstances.

To quote from the JCQ guidance (refer to the ):

Whether an adjustment will be considered reasonable will depend on a number of factors which will include, but are not limited to:

- the needs of the disabled candidate

- the effectiveness of the adjustment

- the cost of the adjustment

- the likely impact of the adjustment upon the candidate and other candidates.

An adjustment will not be approved if it:

- involves unreasonable costs to the awarding body

- involves unreasonable timeframes

- affects the security and integrity of the assessment.

This is because the adjustment is then not 'reasonable'.

Adjustments for candidates with disabilities and learning difficulties, JCQ

In most cases it will not be considered reasonable for adjustments to be made to the assessment objectives within a qualification. To do so would be likely to undermine the effectiveness of the qualification in providing a reliable indication of the knowledge, skills and understanding of the candidate. For the same reason, there is no duty to make adjustments to competence standards within vocational qualifications.

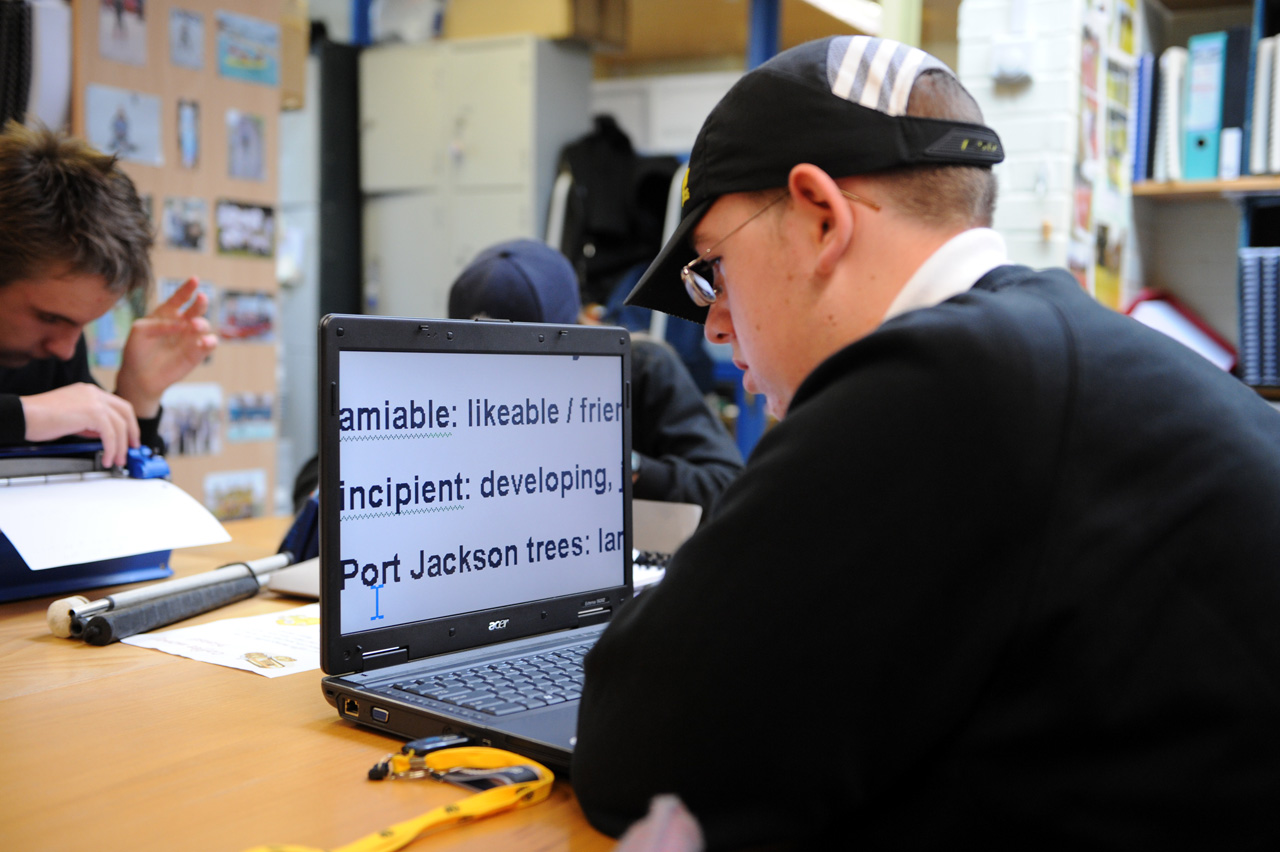

It is vital to ensure that normal classroom practice from the beginning of a learner's education reflects the range of access arrangements which will be available when the formal assessment time arrives. This includes modified language in the classroom, modified curriculum materials in accessible formats, support from a Communication Professional where appropriate and extra time in assessments if these will be requested later, as well as appropriate arrangements for specific tasks, e.g. the speaking and listening elements of modern foreign languages (MFL) or practical assessments in science.

A key principle of access arrangements in external assessments is that any request must reflect the candidate's normal way of working in the classroom and must not just emerge at the time of the assessment. Thus candidates should be familiar by the time of the assessment with the access arrangements they are going to use. Of course, 'normal way of working' is only acceptable if it does not undermine the basis of the examination, as explained above.

While the vast majority of courses will be suitable for a learner with sensory impairment who has the appropriate academic ability, it is important to understand that embarking on a course does not automatically mean that the qualification at the end of it can be made accessible. Teachers of children and young people with sensory impairment need to support these learners at all stages and not just at the time of the assessment.

This support includes ensuring that learners choose appropriate courses and that suitable forethought is given in advance to any potential barriers in the assessment process and how these might be minimised or removed.

A key aspect of the provision of access arrangements is the need to preserve the integrity of the qualification. This means that some arrangements carry greater risk than others. In particular, the use of human support to be carefully controlled to ensure that what is assessed is the candidate's own knowledge and understanding. For example, Language Modifiers and Communicaton Professionals, although they have to record the interventions they have made, are making them during the exam itself so it is difficult at the time to be sure that the arrangement is being applied fairly.

These are therefore 'high risk' arrangements which, if not properly applied, could advantage or disadvantage the candidate, unfairly in either case.

Similar considerations might apply to the use of a practical assistant to support a blind candidate's access to practical assessment — the assistant must only carry out tasks which are not considered to be an integral part of the assessment itself. In such cases rigorous criteria are applied and full recording of interventions made must be provided by the centre. Such arrangements will also need to be separately invigilated and/or take place in separate rooms.